* Council charges householders garbage rates even when the service is not used; cafe, commercial properties choose their private contractors, pick up frequency and shop around for prices

“Chief financial officer Paul Binfield [from Cleanaway] told analysts there would be consistent revenue streams from these [council] projects, and long term bank funding.”

The Australian Financial Review, February 2022

Garbage collection in my Sydney street is my weekly horror.

To my neighbours their garbage is normal and essential. To me it’s a major cause of evermore catastrophic floods, fires, droughts.

Australian local councils have locked themselves into decades long contracts with a few garbage companies which control over 90% of garbage. What I want to do is get food waste out of our street’s garbage. That’s one way we can stop the pollution and destruction of Earth’s atmosphere.

Decades ago, I visited a council garbage dump to get some compost. I said to the compost seller, whose business was near the dump exit gate, “Your compost is made from the garden waste people bring here, right?”.

He laughed and his reply sticks with me, “Sure thing. We get you coming and going, don’t we?”

I reckon I have to change how my neighbours see garbage. My other task is to find a way to free us all from our council’s abuse of its monopoly power over household garbage.

Weekly garbage is the biggest contributor to the pollution that causes huge fires, floods and droughts.

The United Nations graphic below shows food waste is the third biggest contributor to the pollution collapsing our climate, seasons and ways of life.

• Food waste is the world’s 3rd top polluter, after China and the United States

We can tackle climate pollution street by street when we deal with our food waste.

If we eat three times a day, we get three chances to end food waste pollution. We don’t need to sell the family car or put in solar panels – all we have to do is compost our wasted food.

No food waste has left my house since I bought it in 1978, and I’ve composted all my life. Already, using compost bins in our footpath gardens each week, our Chippendale households and cafes are composting over 300 kg of food waste. We’re stopping over 750 kg of climate pollution each week

Composting 1 kg of food waste prevents at least 2.5 kg of climate pollution.

I don’t know if the mother in Lismore, NSW, Ella Buckland, who wrote in a recent article, “I wasn’t ready”, is composting, but her horror story sticks with me:

• Ella Buckland and her child standing in the flood; The Guardian 23 February 2023

“The rain was beating down hard on the tin roof – harder than I’d ever heard in my life. I went out on to mum’s front deck. What I saw and heard will stay with me for ever.

A lake was encroaching, steadily moving up the road. Above the roar of the rain and helicopters buzzing, I could hear children screaming and voices crying: “Help! Help!”

My daughter appeared next to me. “What’s that noise, Mummy?” she asked. “Why are those children screaming? Will someone help them?”

This wasn’t a moment I expected to have, living in this country. I wasn’t ready.”

I feel growing dread about things lost from our street. This recent email describes what’s happening here and in towns and farms across Australia:

“Hi Michael

A number of people in our area have been noting the lack of bees in recent months, and the destruction of hives due to the Verroa Mite is of great concern.

I wondered whether there is a need for us to do more to promote native bees?”

I replied:

“. . . farmers I know out west in NSW, Qld, report that insects are now rarely on their windscreens and they compare today’s windscreens with those they observed a couple of decades ago where it would be common to stop on journeys to clean the windscreens of insects.

In Chippendale where I’ve lived since 1978 these birds and insects are no longer here or are seen rarely (some feed on insects, flowers):

• Bogong moths (gone);

• Butterflies (rare);

• Smaller birds (little wrens for example) which inhabit small, dense shrubs;

• Willy Wagtails (gone);

• Some birds which used to fly down and back from Papua New Guinea.”

Children here will never see those birds and insects. What they don’t see is ‘natural’ to them because that’s what they’ve grown up with. They don’t know they live in a poorer Earth than the one I’ve enjoyed these last seven decades; that once it was far richer with birds, animals and insects, mostly gone.

Stopping our food waste pollution is one powerful way neighbourhoods can save the remaining birds and insects and other life here, including our own selves.

In her 1962 book, Silent Spring, Rachel Carson substantially changed worldwide how many of us saw Earth’s environment and pollution, particularly in the U.S. Carson wrote about the disappearance of birds and insects in the U.S. and identified the cause as pesticides like DDT which kill birds, insects, aquatic life and cause cancers in humans. In response, the chemical industry and their employed scientists created a public vendetta against her and she:

“. . . was discouraged by the aggressive tactics of the chemical industry representatives, which included expert testimony that was firmly contradicted by the bulk of the scientific literature she had been studying. ”

Carson’s fiercest critics were companies profiting from selling DDT and other chemicals that kill insects and birds, but Carson had DDT prohibited from agricultural use by the US government and her book spurred the creation of the modern environment movement.

DDT, however, is widely used across Earth. Fifty seven years later, in 2023, Australian farmers and councils use DDT and other pesticides which accumulate in soil, vegetation, insects and animals. Australian regulators and councils promote, authorise and use DDT, and the mainstream media ignores it.

Global insect populations have declined on average by 41 per cent in the past 40 years.

But some Australian farmers and citizens heed Carson’s science. For example, “For the past 26 years, James Sweetapple has introduced more than 700,000 insects to his winery to repair the environment and reduce chemical use.”

Australia’s local councils, regulators and the few companies which own and control most garbage collection all fiercely defend, promote and are heavily financially and administratively invested in the garbage system.

The system does not reduce garbage or food waste. Those running and profiting from it ignore overseas systems which have succeeded in ending food waste and reducing garbage.

Dozens of U.S. states and thousands of villages and cities have ended food waste and substantially reduced garbage. There, if you don’t put out garbage you don’t pay for a service you don’t use: as a U.S. intern working with me, Marie Neubrander, wrote:

“. . . [with pay as you throw] the less you throw, the less you pay. This heavily incentivises waste avoidance: when we are paying for our waste, we are more likely to attempt to generate less of it (e.g. buying in more appropriate quantities, using safe-to-eat food we might otherwise throw out, etc.). For waste that cannot be avoided, PAYT encourages recycling and/or composting.

These benefits of PAYT are not just theoretical: PAYT has already been implemented in numerous cities and towns across the world, including over 7,000 in the United States. Estimates of the actual quantities of waste reduced by PAYT systems are promising. A 2006 EPA report found that as a whole, PAYT reduced residential trash disposal by 17%. However, this number may be notably higher dependent on community. For instance, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection estimated that communities implementing PAYT reduced waste by 40 to 55%.”

Australia’s parliamentary and consulting reports ignore successful overseas systems. The 2022 NSW parliamentary inquiry into waste did not mention the wonderfully successful laws, policies and job-creating solutions in the U.S., nor did a consulting report to the NSW government in 2019.

A few companies own most of Australia’s garbage business. They control the content of, and profit from, local and state government garbage policy, particularly food and garden organics waste (“FOGO”). (As the data below shows, FOGO is a decades-long and growing climate disaster.)

Where I live, Sydney, Sydney City Council garbage workers are striking. As garbage piled up last month the mayor wrote a hand-delivered note to households:

“Industrial action being carried out by staff of the City of Sydney’s domestic waste contractor, Cleanaway, has impacted domestic waste services . . . Like an estimated 95% of local Councils in NSW, the City contracts an external waste contractor to help deliver the best services possible for the community.”

These are politicians’ and bureaucrats’ favourite words, which I rephrase as, “I’m not to blame, the contractor and workers are.”

In 2022 Sydney council contracted with Cleanaway to take garbage away until 2032 with provision to extend it longer. The contract is here.

Last year Cleanaway invested $2b to buy land in Victoria and Queensland and build “waste to energy’ plants there. These plants burn food for energy. It says the plants will be running by 2027 and:

“. . . about 85 per cent to 90 per cent of revenue will come from gate fees paid by those transporting waste into the sites. Another 10 to 15 per cent of forecast revenue will come from the sale of electricity to outside customers”

The Australian Financial Review, 2022

So powerful are Australia’s largest garbage businesses such as Cleanaway, that they control state government waste planning policies and invest confidently, aware of future policies as far out as 2030, many of which are yet to be publicly announced. For example, in August, 2022, Cleanaway said it:

‘. . . plans to shift the compost operations of newly-acquired western Sydney group GRL into an indoor hall to stop the smell, as it positions for a shift to a four-bin household model in NSW by 2030.”

Cleanaway is an Australia-wide garbage contractor for 130 local councils, 150,000 business customers and runs 5,000 garbage trucks. Revenue was $3b last year. With another contractor, Suez, these two companies handle 94% of NSW garbage.

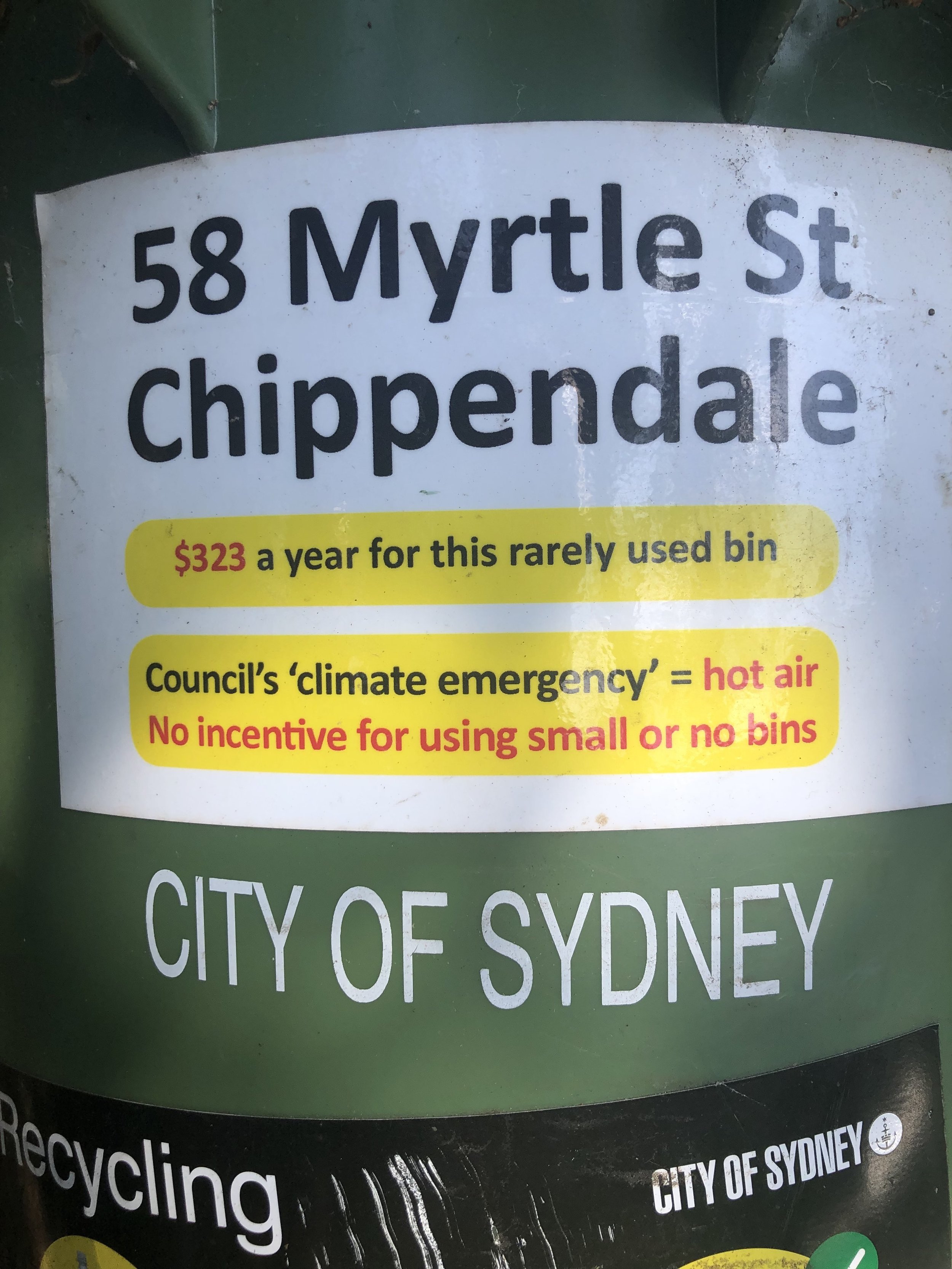

Councils abuse their monopoly garbage powers by making us pay for collection even if we don’t put out garbage. There’s no financial reward for households changing their behaviour and ending our food or other waste. Even where a small garbage bin may be offered with a lower garbage rate and is not used, councils abuse their monopoly powers by charging a minimum garbage rate.

Australia’s garbage market is dominated and controlled by contractors whose business model and market domination controls both council and the state agencies which regulate councils, including the various environment agencies.

Garbage rates are set by councils using their monopoly pricing power. Unlike residential flats, cafes, offices and businesses, householders can’t choose another garbage service provider.

An outstanding failure is the NSW Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal which keeps upping council garbage rates without referring to the successful reduction of market abuses and use of user pays pricing in the U.S. garbage sector.

Monopoly abuse by councils and contractors is most obvious in the food waste method called, FOGO. It works like this:

• Councils say FOGO will reduce climate pollution caused by food or garden waste decay caused by traditional garbage practices;

• Ratepayers are given free FOGO bins to put their food or garden waste into;

• Council or contractor trucks collect the bins and turn some of the waste into compost or burn some for energy;

• The contractor sells the compost or burn food to make energy to sell;

• Local councils do not reduce garbage rates for property owners who volunteer or are forced to participate in the FOGO process.

• Councils get no share of those profits.

Of 26 feedstocks used to burn for energy, food waste is the fourth most inefficient feedstock.

The high prices and market abuses in Australia’s garbage industry smell more than the smelliest garbage dump. The smell is increasing, fanned by the puerile failure of the regulators.

Michael Mobbs